I believe that different creative skillsets can compliment each other to produce more effective creative work. This is joined up thinking.

How it works

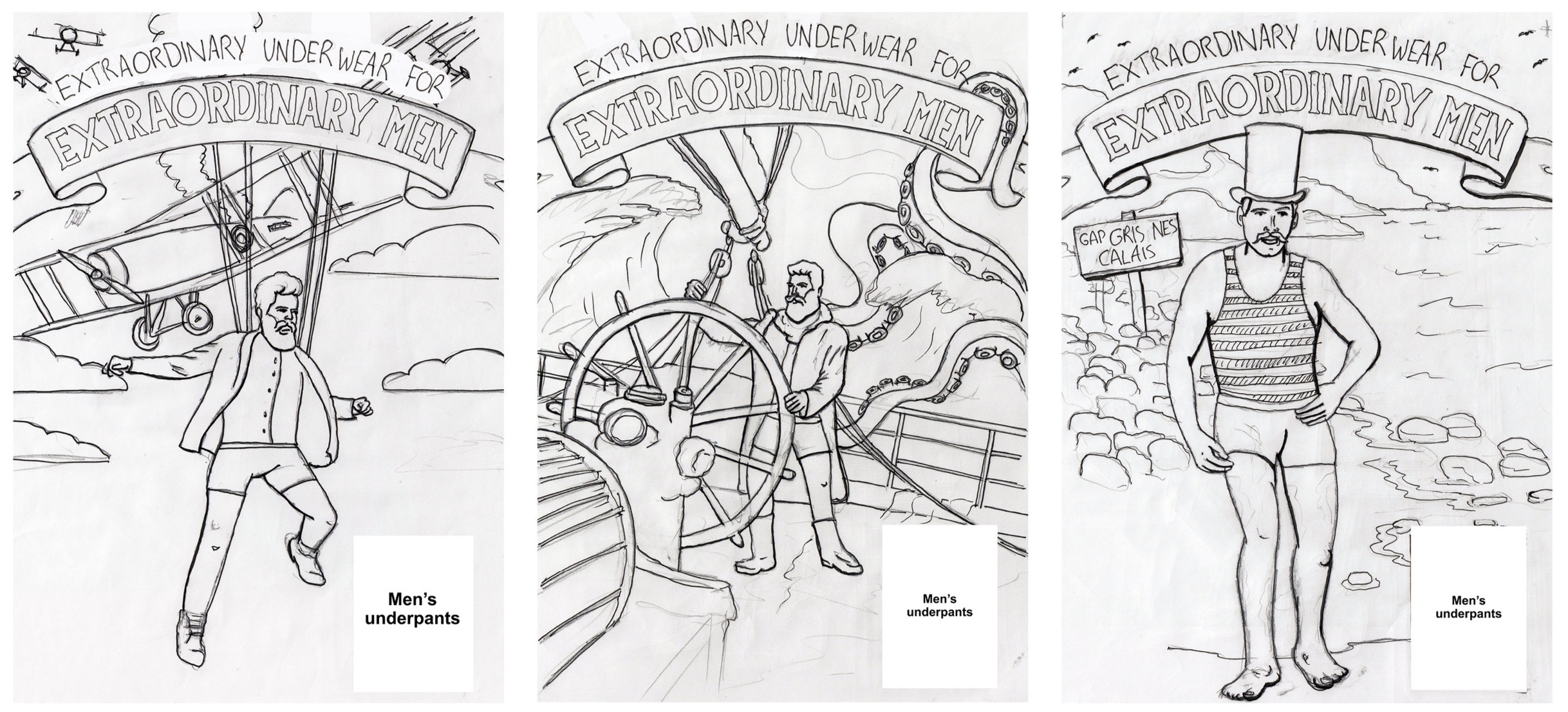

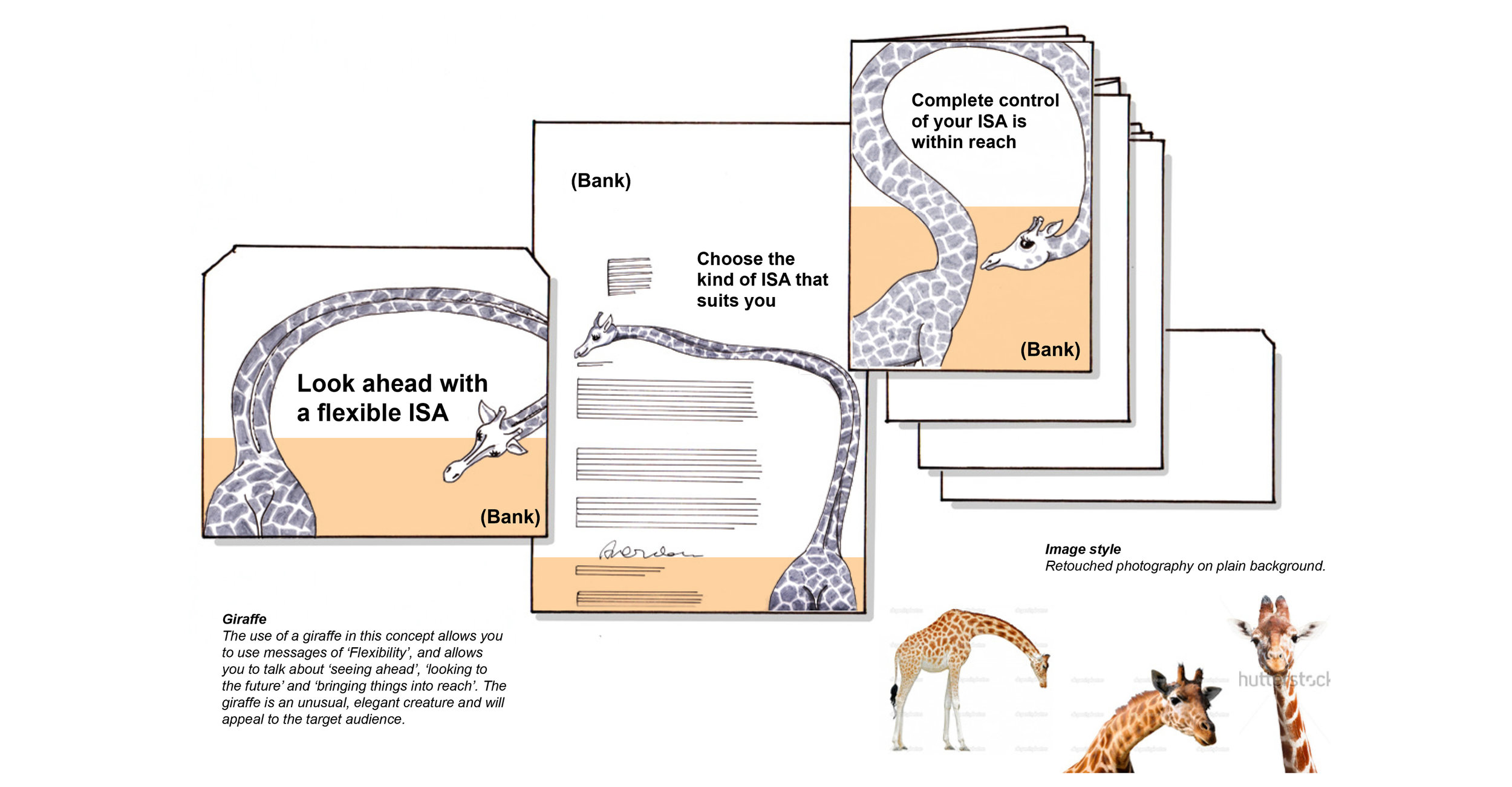

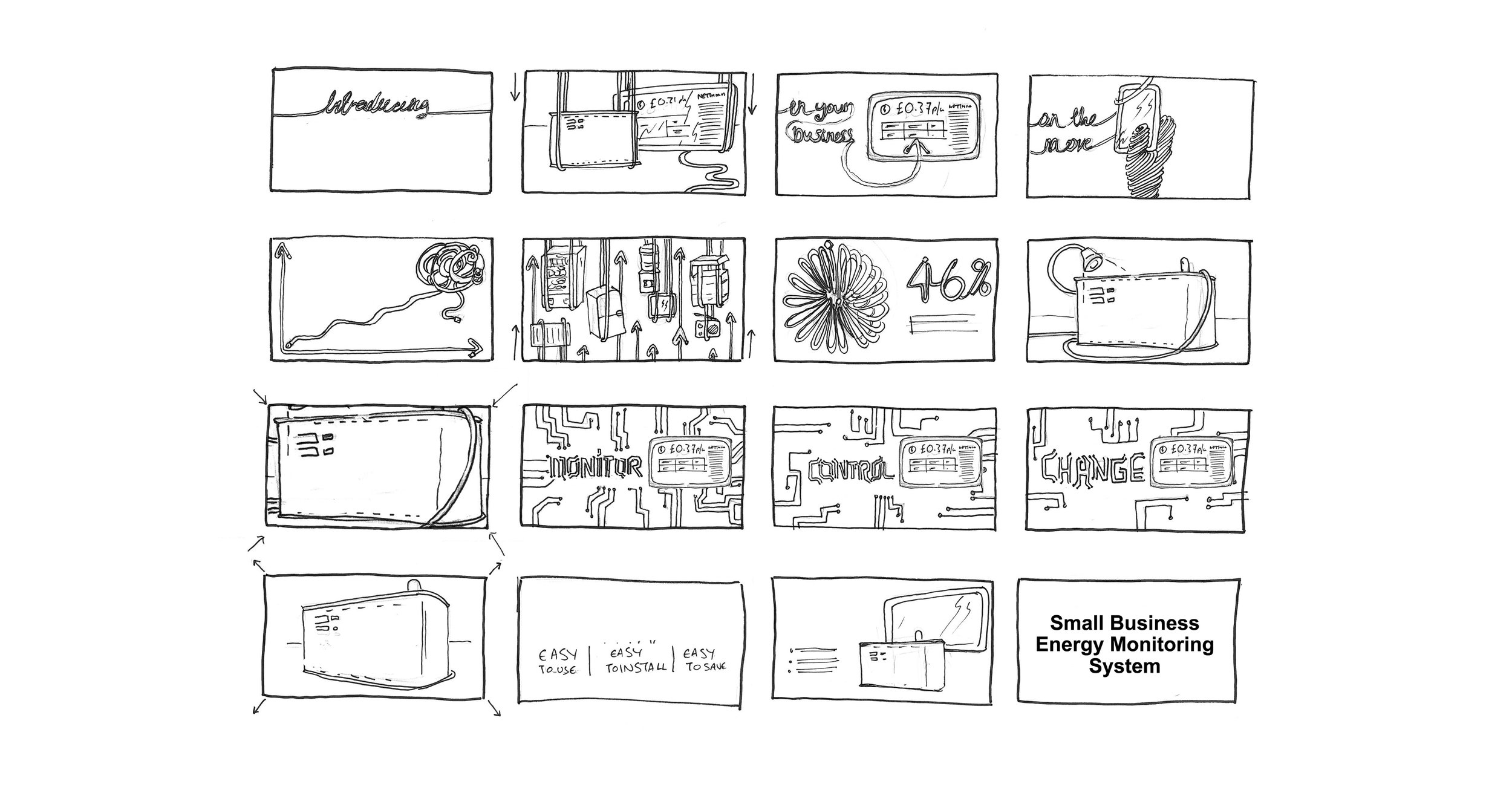

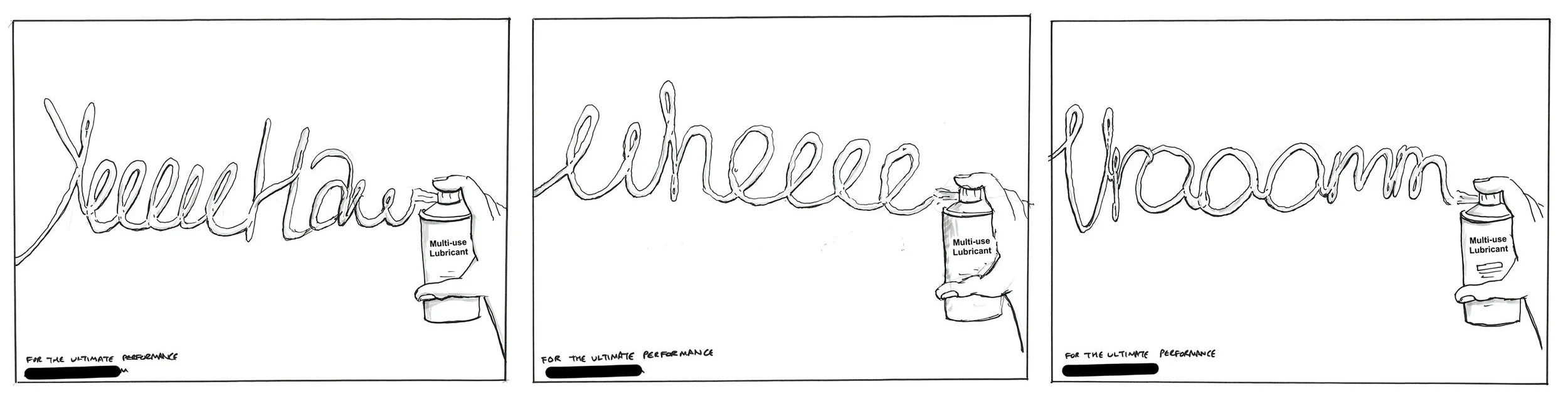

I use a few different skillsets to make the overall service stronger. For example, crafting visuals with a designers’ eye can improve the art direction of ads. Knowing how reveals and messages are structured through direct mail can help make more impactful print design projects. And applying the same level of rigorous thinking to all projects as you would to an advertising campaign makes it all better.

This is how I work. I have built strong skills in various aspects of creative craft, from art direction and concept generation, to graphic design, video editing and illustration.

What this means for clients

I’d like to think I’m less likely to say ‘That can’t be done’, and I can take ownership of more project elements, and can bring them seamlessly into my workflow. I don’t have to brief as many tasks out, and I can maintain the passion you only really have when you’re working on an idea you have developed yourself, and that you truly believe in.

For clients this means I can do more for you, with more dedication, more efficiently and more cost-effectively.

When it started

In my early years in the industry I met a lot of Creative Directors and Heads of Art or Copy in advertising agencies who were at the top of their game. I learned loads of really useful things, but I kept getting a piece of advice that I couldn’t really get to grips with. It was something like this, ‘Be a specialist, you can’t be an Art Director AND a Designer, they’ll think you’re a Jack-of-all-trades’ or similar words to that effect.

I get it, it’s much easier to remember someone who is ‘Andy the Art Director’ than ‘Andy the Designer, Art Director…etc…’ But apart from being easier to put in a box, the idea never sat well with me. I didn’t want to just do one thing. I had too many ideas I wanted to bring to life, and I felt that other creative skills could only help make the work better. It seemed like a no-brainer to me.

As my career progressed I met more like-minded people, art directors who could also illustrate, designers who could code, copywriters who were also cartoonists, filmmakers who were also musicians... I recognised that there were two ways to go about things. You can stick to one thing, hang your hat on it and aim to be the expert at that, or you can expand and build complimentary skills and use them to make everything better.

Knowing your limits

There are some things I have either avoided, or tried and realised I’m just not cut out for. For instance, I’m never going to be a web developer. I understand what makes websites enjoyable to use and look superb, but I’ve tried to teach myself coding three times and thrown the towel in. I just don’t have that kind of brain.

Likewise, for animation and motion graphics. I do a bit of it, but more to make the films I make more interesting. I think this an area where specialism is important. Mastering animation is too time consuming to do alongside everything else. I have seen other people dedicate the focus and time needed to get really good at it, and I know I won’t want to stop learning other things to get good enough for that.

Copywriting? I love it! It’s what I wanted do when I first started in advertising, and I’ve won awards for it. But whilst I can write headlines, messages and scripts, I recognise the true craft of copywriting requires a more sophisticated grasp of the English language. You need to be able to write long, structured copy in any tone of voice. And it all needs to be perfect, so that grammar pedants won’t spot mistakes. I know a lot of people who are master copywriters, and it’s a craft I really respect.

Fortunately, I have a network of trusted professionals. Expert specialists who I collaborate with on projects, including copywriters, animators, illustrators, photographers and web designers. So I can bring them in to help me tackle almost any creative challenge.

It all comes down to the idea

My approach is to invest energy up front developing really strong, effective concepts. Then I can let the idea dictate the creative decisions - each skill should be working to bring the idea to life.

This makes every other part of the process much more efficient and much more exciting. In turn, you have more focussed, single-minded, concept-driven work, which is more likely to resonate with people.

Find out how Joined Up Thinking can help your business today.